The following 975-word text is excerpted from the book’s second section entitled “The Vietnam War” and a chapter entitled “Leaving Home: The Party’s Over.”

Nestled on the south shore of eastern Long Island, N.Y., Westhampton has always been in my blood. Indeed, my mother took me there for the first time when I was two months old, and I make my summer home there today. My maternal grandparents first frequented the area in 1928 when my Mom was only six. The ocean beaches there are among the most beautiful on earth, and it retains many of its rural qualities, despite substantial development in the post-World War II era. As young children, my brother and I, and also our four younger sisters in pairs, would spend a fortnight with Mimi and Poppa in their cottage at Cedar Beach on shimmering Moriches Bay, part of Great South Bay.

In June 1968 Mame and I took our infant son Chas to Cedar Beach for a few days of vacation before I shoved off for Vietnam. All those wonderful, golden days I had spent there during my then twenty-three years flooded my mind. Fishing and crabbing with my brother Mike, the salt air, the musty scent of the cottage, its coziness, Poppa’s Chuck boat, the main house where we took our meals—these familiar sensual experiences and physical structures had always been revisited and renewed each year and gave me a generous measure of joy.

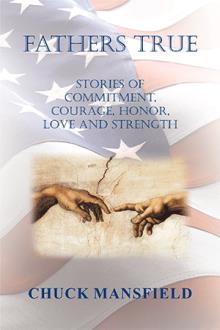

The new father and infant son Chas at Cedar

Beach in Westhampton on June 22, 1968, five

days before Marine Dad deployed to Vietnam

(Photograph courtesy of Mary Ann Mansfield

and used with permission)

With now only Vietnam ahead of me, I wanted to block it and everything else out of my mind, except my beautiful bride, our baby boy and the old-new wonder of Westhampton. I remember only the love I felt and would miss in the as yet unknowable year ahead.

Although the weather was very cool, too cool for the beach, I am sure we found plenty to occupy ourselves; after all, Mame’s fertile mind and imagination have never failed in the realm of good ideas. Nonetheless, my memory retains little about those precious days other than my strong desire to remain right there at the little cottage on the bay.

So many significant and, for that matter, insignificant dates are etched in my memory that some people occasionally call me “Rain Man,” after the character played by actor Dustin Hoffman in the title role in the film of the same name. Why, then, I do not recall with certainty the date on which I left home for Vietnam, I am at a loss to say. Suffice it to say that it was on or about June 27, 1968.

My orders indicated that I would travel to Norton Air Force Base in San Bernardino, Calif., “FFT,” that is, “for further transfer,” to “WestPac Ground Forces.” WestPac was a contraction for “Western Pacific” but invariably meant Vietnam, at least at that time.

My journey began at my parents’ home in Garden City (GC). My sister Peggy, then 16, was seated in the living room recliner holding my son Chas, not yet three months of age.

I had no wish to leave but I was as ready to go as I was going to be. Mame and my parents were readying themselves to take me to New York’s John F. Kennedy International Airport, about a twenty-minute drive. There I would meet my flight to the West Coast FFT.

The moment had arrived. I walked over to Peggy and the baby, each still comfortable in the big recliner. I kissed her goodbye. When I kissed Chas, I said, “Goodbye, little fella.” Well, Peggy, Mom and Mame all began to wail. It was awful. Then I recall Dad saying, “Let’s get the hell outta here” but his voice somehow lacked its usual “Now hear this” fanfare.

The ride to JFK was understandably unenjoyable. Dad was driving, and Mom sat next to him in the front seat. Mame and I sat behind them. There was little conversation. The ladies were choking back tears; Dad was characteristically silent, as he had long since relied on the women to do the talking in many social situations. I was hurting but would be damned before I would let on.

Having arrived at the airport, I said goodbye to my folks, and Mame accompanied me to the plane. As there were no security checkpoints in those days, we strolled slowly and directly to the door of the aircraft. There we hugged and kissed, maybe thrice. She was tearful, and I was dying inside. I had to get on that plane, sooner or later, never mind having no remote wish to do so.

We left the comfort of each other’s arms, and I turned away and boarded my flight. As much as I wanted to take in the sight of her beautiful face once more, I knew I dare not turn around. I made up my mind that I would walk, face and eyes rigidly forward, straight to my assigned seat on the port side near the front of the plane. Had I looked back, my own tears would surely have flowed. As it was, I sat down, closed my eyes and composed myself. After all, a man goes to war by himself.

As my decades-long friend and brother Marine Bob Lund used to say when daunting responsibilities presented themselves, “The party’s over.”

Once more the pessimist, although I never breathed a word of it to Mame or anyone else, I did not believe I would come home from Vietnam alive. In truth, this pessimist actually thought he would never see his beautiful bride, his son or his homeland again. It was scary.

With greater resolve than ever before, despite my unprecedented and possibly unhealthy state of mind, I told myself it was time to get serious.

The party was over.

Au revoir, mon amour.