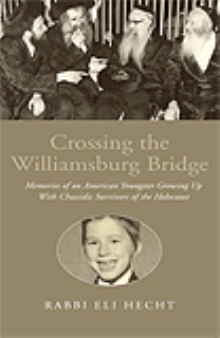

By way of introducing my readers to a special world, often known only to the Orthodox Chassidic Jewish community, I have elected to share my experiences as an eight-year-old American boy.

I am the third of nine children, the oldest boy and named after my deeply Chassidic great-grandfather, Eliyahu. It was thought that in order for me to give honor to his name, I should be exposed to the lifestyle he and his family lived.

As a young child I was moved from a modern American Orthodox home to my grandparents' home located in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, New York. There I met a new type of Jew, Hungarian Jews, refugees from Europe. Many had their children born in "displaced persons" (DP) camps. They had just arrived with their families in New York after a hard-earned escape from the Russian suppression of Hungary in 1957.

While living with my grandparents, called Upa and Uma, I learned how to live and dress in a Chassidic manner. I learned to love my teacher, called Rebbe, and my classmates.

In the 1950s almost all of my classmates were children of the infamous Auschwitz deportees from Hungary. Most teachers had branded tattooed numbers on their arm, physical reminders of inhuman cruelties.

I remember visiting a family with my Uma and being told by the mother, "How lucky you are, yingele (sonny-boy), that you have a father, a mother, a brother, a sister, uncles, aunts and even grandparents. The only thing I have left from Germany is this!" She shoved her arm with the blue numbers in front of me.

Other times, my Jewish teacher, a survivor of the camps, would cry in class, thinking of the suffering he and his family had experienced. Many of the school children were from second marriages. Either their father's or mother's first spouse had been killed. It wasn't uncommon for children to have half brothers and sisters who were 10 or 15 years older than they.

As long as I can remember there was hardly a religious holiday or happy occasion that didn't end in a funeral speech for the family members who weren't there. Every newborn baby, Bar Mitzvah, or wedding party that I attended had a discussion about a dead or martyred parent. The newborn child was always named after one of its parents' deceased mother or father, sister or brother. Households of that generation persisted with fear of death and persecution.

It was very frightening to hear my traumatized teacher tell us how an SS soldier would, at times, give an extra morsel of bread to a child, and then shoot the children who stepped out of line asking for bread.

As I grew into a teenager, I visited friends in their homes. Invariably the conversation would rotate back to the war years. Parents who were survivors of the Holocaust would point to me and say, "Look at this American. I had a son just like him. How old are you?" I would state my age. "Yes, that's about how old my son would be, but he was killed in the camp." Another would ask, "How many brothers and sisters do you have?" After answering all their questions, they would say, "Lucky you! I had that many family members but most of them were killed before their Bar Mitzvah age." I became very sensitive to their cries of misery and untold misfortune.

I strongly feel the need for people to understand the Chassidic community. How, as survivors of European Jewry, they rebuilt a vibrant community. Their way of life, thought destroyed by Nazism and anti-Semitism, has been preserved. Their mode of life lives on in Brooklyn, New York.

However, their lifestyle is still a mystery to many. So this book will help you understand the Chassidic world and dispel many negative stereotypes of Chassidim. In presenting my few years living in Williamsburg, old questions will be answered and new ones asked. Interesting lifestyles will be illuminated.

Living in Williamsburg made me different from other American Jewish children. I changed from an all-American child who dreamt of Sandy Koufax, my childhood hero, and reading Superman comics, to a little Chassid. Turbulent but important years they were to me.

When looking back I know for a certainty that those short, few years have had an indomitable effect on me. Being immersed in a Chassidic community makes Judaism real, vibrant and not a religion of the past.

This is the story of growing up into a Chassidic child and my later years as a Chassidic rabbi in Lomita, California. I include stories of my family and other beloved people who were outstanding examples of dedication to Yiddishkeit - the Jewish way of life, giving us a message that we can live meaningful lives by embracing traditional Judaism.

I also included poems and articles that are a kaleidoscope of Jewish life. This completes the circle for the many people who haven't had a chance to learn about our noble heritage. Over the last fifty years, thousands of people came and went to Chabad. When entering Chabad they feel at home and welcomed. Some have returned with children and grandchildren. They recognize Chabad's contribution to the growth and existence of Judaism. You, too, my dear reader, are welcome to visit.

In the last part of this book I speak about my father's family which is made in America, in contrast my mother’s European family, leaving us with the message that you can be an American Jew and keep the tradition of the old.

My memories of holiday stories during the Holocaust conditions sensitized me to have a strong belief in G-d, giving me faith that cannot be explained or understood.

"For those who question G-d there are no answers, but for those that have belief in G-d, there are no real questions." This is something I learned living in Upa and Uma's home in Williamsburg.