Preface

Remember, kid, there’s heroes and there’s legends. Heroes get remembered, but legends never die.

—David Evans, The Sandlot

Tears roll off Willie’s cheeks. Members of the audience shoot quizzical looks at tablemates and friends in the crowd. They never expected to see Willie like this. Not with so much meaning, so much passion. So emotional. Throughout the room, napkins and handkerchiefs dab at the corners of moist eyes. Servers and busboys stand in rapt silence.

The hushed ballroom is packed. Hardly surprising. Willie, Mickey, and the Duke are being honored here this night. What baseball fan wouldn’t want to see such baseball royalty all in one place?

It is the first time they have appeared together in public since the 1956 All-Star Game, when Mickey started for the American League and homered off Warren Spahn. Willie and Duke were reserves for the National League.

Twenty-two years later, they assemble at the New York Sheraton Hotel, where the Baseball Writers Association of America is announcing its new award—The Willie, Mickey, and the Duke Award.

Willie pauses for a moment to compose himself. “People ask me all the time how I want to be remembered,” he says. “Most of the time, I say what they want to hear: That winning two MVP Awards was great—but I know there’s a new MVP Award every year. Hitting 660 home runs was great—but someday, somebody will hit more. But this, this award, this is a special way to be remembered. It means the three of us will always be here together, forever, even after we’re gone. I’ve seen awards named for others like Hank and Roberto, but I never thought one would be named for me. I have always doubted that I was ever really loved.”

Many in the room are stunned. Did Willie really think we didn’t love him? Our Willie? That can’t possibly be. Here he is, this beloved living legend, questioning his place in the baseball pantheon. Say it ain’t so, Willie.

Mickey is next to take the podium. “I always swore that following Maris in the batting order was the toughest thing I ever had to do in baseball,” he says, looking at Willie. “Until just now. I can’t count the endless number of times I’ve been asked who was the best when all three of us played center field in the same city and owned center stage in Series after Series.”

He puts his hand on Willie’s shoulder and says, “You were the best, Willie.”

A tear rolls down Willie’s cheek.

Mickey turns to Duke. “I don’t mind being tied for second with you.”

Duke smiles.

“Do you agree? Duke?” someone calls from the audience. “Who do you think was the best?”

“Joe DiMaggio,” he deadpans.

To conclude the ceremony, Terry Cashman, former minor league player in the Detroit Tigers system but now known as the Baseball Balladeer, sings his song “Talking Baseball” with its popular refrain:

They knew ‘em all from Boston to Dubuque.

Especially Willie, Mickey, and the Duke.

Those were the days.

This is the last time the three great center fielders will appear together. Before the year is out, Mickey will die after liver replacement surgery.

Introduction

And history becomes legend, and legend becomes history.

—Jean Cocteau

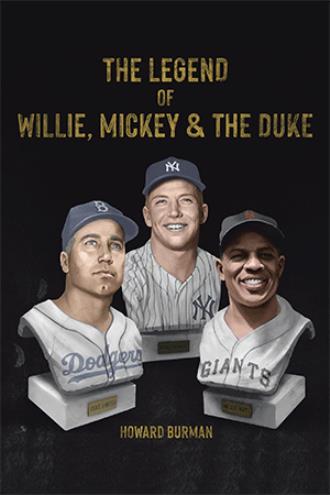

Their names are intrinsically linked. Willie, Mickey, and the Duke go together like baseball, peanuts, and hot dogs. Think of one, think of all three.

Three men, one game, one position, one city. Three of the greatest center fielders ever playing for three different teams within a few miles of each other.

Position by position, comparisons were a regular part of the New York baseball fandom in the 1950s when baseball was still king of American sports. One of the accepted axioms of baseball is that for a team to be good, it must have strength up the middle—catcher, second, short, center field. The three New York teams of the ‘50s all did. In Brooklyn, it was Campanella, Reese, Robinson, and Snider. The Yankees had Berra, Rizzuto, Martin, and Mantle. For the Giants, Westrum, Dark, several second basemen, and Mays manned those positions. Mays, Mantle, Snider, Reese, Rizzuto, Campanella, and Berra are all in the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Center field has always been a pivotal position. The quarterback of the outfield. The man who catches anything he can reach. He had to have a strong, accurate arm and fleet feet. If he could hit with power, so much the better. Willie, Mickey, and Duke could run, throw, and hit with power.

Always peers, never close friends, they were acutely aware of the constant comparisons in the press and among fans. Who was the best center fielder: Willie Mays, Mickey Mantle, or Duke Snider? And not just who was the best center fielder in New York, but who was the best center fielder in the world? An argument could be made for each.

Good, great, greater, greatest. The debate was endless. Other good center fielders were at their peak in the ‘50s—among them, Larry Doby, Gus Bell, Richie Ashburn, and Jimmy Piersall. But none reached the levels of Willie, Mickey, and the Duke, who reigned supreme throughout the decade and into the ‘60s.

In earlier years, Ty Cobb, Tris Speaker, and Joe DiMaggio would rank among the best at that position, but they didn’t play during the same years. Cobb and Speaker were contemporaries. Cobb was recognized as the best player of his era. Some claim Speaker was the best defensive center fielder—ever.

Any assessment of who the greatest center fielders of all time are is a matter of observational and data-driven speculation. There is no right answer. However, it would be difficult to say that Mays, Mantle, and Snider aren’t all in the top ten, along with Cobb, Speaker, and DiMaggio from earlier years and Ken Griffey Jr. and Mike Trout in the years since. The order can be debated, but their inclusion can’t.